by David Denham.

The Newcastle Museum recently commemorated the 1989 Newcastle Earthquake with an exhibition dedicated to all those affected by the earthquake that caused the deaths of 13 people in Newcastle and massive property damage estimated at approximately $1 billion.

The Now and Then Exhibition which closed on 8 February 2015 attempted to portray what has changed since 1989 through the eyes of over twenty people who were affected significantly on the day of the earthquake. It examined individuals’ stories of what happened on that day and the recovery to build a more vibrant and cohesive society. After all without the people, there would be nothing much to tell.

My story starts in Canberra. The days between Christmas and New Year are usually good to get your workspace in order and make plans for New Year. I well remember 28 December 1989 starting off like this in the Anzac Park East building. This was a special purpose five storey building constructed for the Bureau of Mineral Resources Geology and Geophysics (BMR). It was completed in 1965 and housed most of the BMR and subsequently AGSO, the Australian Geological Survey Organisation, until 1998 when the agency moved to a new special purpose building in Symonston in South Canberra. Surprisingly, the original building has remained empty since then.

Anyway, at 10:30 am on 28 December 1989, I was sitting on the fifth floor in the Director’s (Roye Rutland) office. This was a temporary location while his permanent office was being re-furbished. It was situated outside the lifts and close to the junction of the two arms of the L-shaped building. I have forgotten what the issue was that required me to be there, but suddenly, the whole building started to shake and you could hear the two arms of the structure grating together as they moved from side to side.

It was obviously a significant earthquake, but where did it take place, how large was it and would there be any damage or casualties?

At the time of the earthquake, BMR’s Seismological Centre was situated near St John’s Church about 100 metres from the main building, so I scampered back to find the Centre in chaos. Only two people were on duty. All the telephones were ringing and the media were desperate for information.

We were getting news of collapsed buildings in Newcastle and still did not know where the earthquake occurred and how large it was. The only information we had on site was from stations in Kowen Forest (ACT) and Alice Springs (via telemetry). We had to telephone seismologists at Armidale and Melbourne to ask them to fax their seismograms; and these were all on the western side of the event the location was very poor. Furthermore, because all the regional Australian seismographs were sent off scale, the magnitude of the earthquake (~5.5) was quickly estimated from the extent of the area that felt it.

It wasn’t until some weeks after the event that we were able to obtain the depth of the earthquake, an accurate hypocentre and an estimate of the faulting mechanism associated with it.

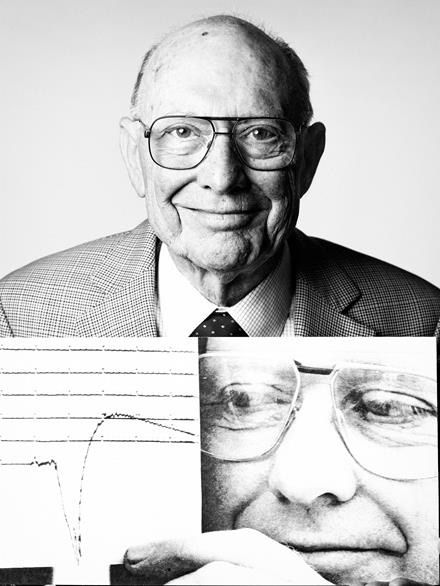

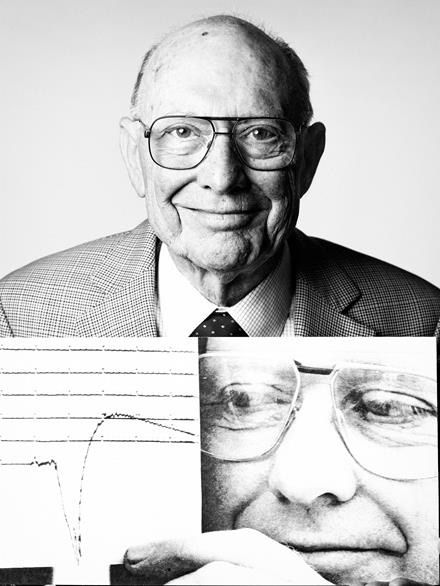

We had a very insensitive seismograph in the BMR building and the record from that instrument is shown in the Figure, to provide the ‘Then and Now’ theme in the Exhibition. Even this instrument, approximately 400 km from the epicentre, was saturated by the amplitude ground motion.

It turned out that it occurred at a depth of approximately 12 km at a distance of 15 km west of the centre of Newcastle, was caused by east-west stress in the mid-lower crust and had a magnitude of 5.6.

Nowadays, the locations, magnitudes and mechanisms for most events larger than magnitude five, can be determined within 30 minutes and the appropriate emergency services advised if they are likely to be needed.

The socio-economic effect on Newcastle was enormous, it impacted on every Novocastrian, and this is the focus of the exhibition.

The socio-economic effect on Newcastle was enormous, it impacted on every Novocastrian, and this is the focus of the exhibition.

It is also noteworthy that ever since Europeans came to live in the vicinity of Newcastle, earthquakes have been felt there. Those having a magnitude of approximately five occurred in 1837, 1841, 1842, 1868 and 1925. However, the 1989 earthquake was probably the largest of these.

State and City planners should be aware of the earthquake hazard when development applications are being assessed in the Newcastle area. The larger the city, the more there is to damage and the exhibits at the Newcastle Museum confirmed f the damage that can be caused from a moderate sized earthquake.

Image: Looking at the record obtained from the basement of the BMR building. The small regular trace offsets are minute marks and the shaking was large enough to saturate the instrument. This record could not be used to locate the Newcastle Earthquake because the time resolution was inadequate. The picture is the Then and Now image displayed at the Exhibition (Image Courtesy of Luke Kellett, Headjam).

Editor’s Note: Cynthia Hunter published an excellent book ‘ Earthquake tremors felt in the in the Hunter Valley since white settlement’. Hunter Publications, Newcastle 1991.